On Thursday, a significant solar explosion hit Earth, leading to a “severe” G4 geomagnetic storm. This event, triggered by a huge mass of charged particles ejected from the sun on October 8, created the potential for auroras to be visible much further south than usual, and could reach areas such as California and Alabama.

Impact on electrical networks and communications

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) warned that this storm could disrupt power grids and communications systems, especially those weakened by recent hurricanes Helena and Milton. The aurora is expected to light up the northern half of the US, with the possibility of seeing it at lower latitudes. NOAA is in contact with federal and state officials to discuss possible impacts on hurricane recovery efforts.

Potential for intensification

There is a chance the storm could intensify into G5 “extreme” conditions, similar to the significant solar event in May that resulted in auroras visible as far south as Florida. As the situation develops, NOAA will provide ongoing updates regarding the storm’s progress.

The nature of solar flares and CMEs

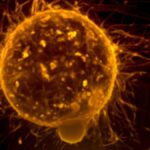

The solar explosion itself is the result of a coronal mass ejection (CME) associated with a powerful X 1.8 class solar flare, which is the most powerful type of flare emitted by the Sun. Solar flares occur when the sun’s magnetic field lines tangle and snap back into place, sometimes releasing fast-moving clumps of plasma that take days to reach Earth. After contact, these CMEs can cause disturbances in the Earth’s magnetic field, leading to geomagnetic storms and stunning auroras. The strength of these storms is measured on a scale of 1 to 5.

Tips for Aurora hunters

For those hoping to catch a flash of the northern lights, experts suggest moving to locations away from city lights to improve visibility. Although no special equipment is required to view the aurora, using a smartphone camera can enhance the colors, making for a more vivid experience.

The context of the solar cycle

The frequency of solar flares, CMEs, and auroras typically increases during the solar maximum phase of the sun’s approximately 11-year cycle of activity. Although this cycle was originally expected to peak in 2025, some scientists believe we may already be witnessing its beginning.

Comet C/2023 A3 in danger

Interestingly, the CME also poses a potential threat to the bright comet C/2023 A3 (Tsuchinshan-ATLAS), which is currently making its closest approach to the sun in 80,000 years. Observers are curious to see if the solar flare affected the comet’s tail, similar to an earlier event involving another comet. The outcome will become clear when C/2023 rises behind the sun this weekend.